As a mother of two young children, nothing pleases me more than watching my children play. I love to observe the inventiveness of their young minds as they stock pretend shops with shells, stones and leaves or fashion imaginary tools from twigs. It’s fascinating to watch as they run about, assume roles or create exciting imaginary, make-believe scenarios with just minimal resources.

My daughter is now seven years of age. She is about to start in KS2 and is considered to be academically successful, although she does not yet write with a pen, or join up her letters, neither does she speak another language. But she reads well, and and her written work is legible. Her punctuation and grammar is at, what I would describe as, a ‘fledgling’ stage. She also has a tendency to spell all words as they sound – which can be problematic. There are also a lot of basic mathematical concepts that she has not yet fully grasped. For example, she does not tell the time very well, and her understanding of distance, weights and measures is limited. Although her arithmetic is quite good, she does not know her times tables. Yet despite all of this, the school report to me that she is ‘above average’ in every single area – and ‘well above average’ in a few.

Thus, she has been at school for three years, and is, apparently meeting and often exceeding their expectations.

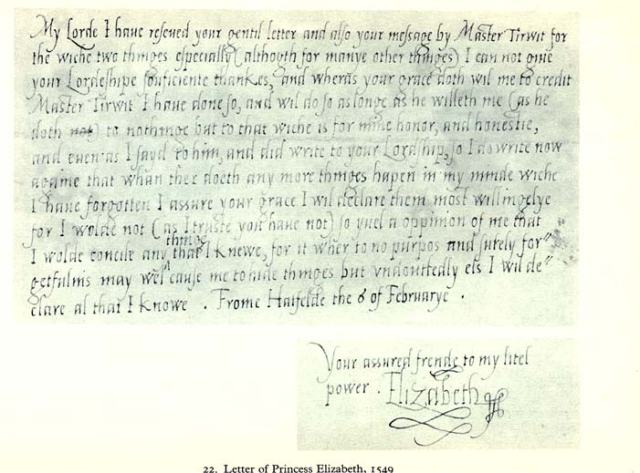

In the early 1540’s when the majority of the population were completely illiterate, a more fortunate child than these was also being schooled. Despite the decapitation of her mother and the absence of a father, Elizabeth I was in the process of proving what heights of academia could be possible, with the right tuition.

‘Elizabeth’s comfort with reading and writing Latin…as well as being fluent in many other languages, would suggest that she began linguistics lessons very early.. Modern studies show that the younger a child is when they learn a second language, the easier it is for them to retain other ones.’

And by the age of fourteen, under a new tutor:

‘Ascham helped Elizabeth to perfect her classical languages through his famed method of “double translation.” For instance, he would present her with the original texts of Demosthenes or Cicero, having her turn them into English, and then translating them back into their original languages …Elizabeth spent her mornings reading from the Greek New Testament, followed by a study of classical orations, and Sophocles’ tragedies. Ascham believed that his selections would help Elizabeth to ‘gain purity of style, and from her mind derive instruction that would be of value for her to meet every contingency of life.

‘Ascham helped Elizabeth to perfect her classical languages through his famed method of “double translation.” For instance, he would present her with the original texts of Demosthenes or Cicero, having her turn them into English, and then translating them back into their original languages …Elizabeth spent her mornings reading from the Greek New Testament, followed by a study of classical orations, and Sophocles’ tragedies. Ascham believed that his selections would help Elizabeth to ‘gain purity of style, and from her mind derive instruction that would be of value for her to meet every contingency of life.

After noon, Elizabeth would study Cicero, and some Livy. Ascham also supplemented these famous works with St. Cyprian, and Melanchthon’s Commonplaces…’

(‘The Shaping of Elizabeth I through Childhood Events and Academic Pursuit‘

Born into less financially favourable circumstances than Elizabeth, Leonardo da Vinci was all-but orphaned as a child. In 1466, at the age of fourteen he was sent to be apprenticed to an artist- ‘Andrea di Cione, known as Verrocchio, whose workshop was “one of the finest in Florence’. Here, he was schooled, not only in the techniques of fine art (in which he soon surpassed his master), but also in engineering, linguistics and mathematics. Obviously a hugely talented man, but it seems that none of these skills were gained without the additional labour of academic study and strict regime.

Now, I’m not suggesting that an Elizabethan, or late-medieval method of schooling is necessarily the way we should be going about things in the modern world. but I do think it’s interesting to consider the possibility that our children may just be capable of far more than we give them credit for, or ever give them the chance to show us.

Under the current system, a varying amount of KS1 education (certainly in Reception and Y1) is devoted to play and discovery learning. Desks are usually arranged in mixed-ability groups – presumably to facilitate this. The national curriculum is followed, and there is a proportion of academic input, but I’m not certain whether it is necessarily given priority over the more ‘creative’ aspects of the curriculum, in all schools. By KS2 and above, there is undoubtably more of an academic focus – but is it enough? Some argue that it might be too much:

Sir Ken Robinson is a widely respected voice on this matter. Often opposing academic regimes, he regularly posits that our modern schools may actually be far too formal and rigid:

‘In Sir Ken’s ideal school, there would be no hierarchy of subjects in the curriculum and classes would not be grouped by age. Dance would be as important as maths, and children would feel free to do what they wanted, even get up and wander around in lessons..

..he would get rid of almost all school exams, suggesting that in chasing certificates we “over-school” and “under-educate”.’

( ‘How badly do we teach our children? Discuss’ Sarah Montague 13 Aug 2014 )

And he has the ear of many modern academics and educationalists on this matter. It seems that many agree with him, feeling that academic rigour, routine and testing are simply stifling to creativity.

But what, then, do we now define as creativity? Does a modern creative curriculum even allow the creative arts to flourish to their fullest degree? Leonardo da Vinci clearly was one of the most creative, innovative and imaginative people who ever lived. Elizabeth I herself was famed for her love of dancing and the arts, and the Elizabethan period itself is responsible for (almost) indisputably one of the most creative literary figures ever – William Shakespeare. But presumably we would have none of those wonderful plays if Shakespeare himself hadn’t been properly schooled in grammar and linguistics. (Indeed,, when there were no words in English to suit his purpose, he made up new ones – 2,000 in fact that are still in use today!) Elizabeth I famously loved to dance and sing outside her enforced periods of academic study, and Leonardo da Vinci did not become the truly great artist, anatomist and inventor he became, without the documented long hours of study and practise.

For my own part, I’ve become more resentful of my academically-lightweight nineteen seventies and eighties education as the years have passed. I regularly wish I’d been given more regular formal grammar and mathematical instruction. My daughter, it seems to me, is faring no better. In the example of her written work, at least, I think she may even be slightly behind where I was at her age. This despite my being utterly convinced that she is naturally more academically able than I was. For children from more deprived backgrounds than her, the stakes are even higher. Academic qualifications are generally acknowledged to be the best ticket out of poverty of all. To deny pupils this opportunity on the basis that academic study, rigour, testing and hard work are somehow cruel and unnecessary could prove to be an absolute travesty for them.

Children love to play. It is also true to say that they are naturally creative. Schools should certainly provide plenty of recreational time for children to explore and discover their creativity. Creativity is also crucial for academic study. Children need to be creative in many academic disciplines – drawing, poetry, Drama and creative writing, for example. However, this is a two sided coin in which the accurate application of creativity depends hugely on acquired knowledge and skills to successfully execute. If we teach children how to draw and write well, if we equip them with the language they need, if we impart the scientific studies of previous generations, if we teach children how to calculate and measure, then they will have truly strong foundations on which to build their academic careers. If we neglect to do this, then they will only have what their limited early life experience has taught them, to build on.

Sir Ken argues that we are doing our children a disservice by ‘over schooling’ them. Surely the opposite is actually the case? I think the purpose of schools is to educate young people in disciplines, and provide knowledge and skills in areas that they may not otherwise discover for themselves. To view learning and academic study as the enemy – the bad guy – might just be a huge mistake. It’s entirely possible that the gift of learning may just be the most valuable gift of all.

Please follow me on Twitter: @cazzypot

Reblogged this on The Echo Chamber.

LikeLike

“but I do think it’s interesting to consider the possibility that our children may just be capable of far more than we give them credit for, or ever give them the chance to show us.”

I agree, but I’m not sure it’s fair to compare two people who would be considered exceptionally able with your average student, nor to compare what pupils in the 15th/16th century were expected to learn with what they are expected to learn today. If most of the curriculum consisted of Greek and Latin, many modern day 14 year-olds would be a match for Elizabeth, and many 14 year-olds would do really well if apprenticed to a superlative craftsman.

LikeLike

I agree that the curriculum is vastly different. I’m simply querying whether kids could perhaps learn more (and earlier!),as you quote above. I think it’s interesting to consider the possibilities. Thanks for your comment, it’s always good to generate a bit of discussion, I think.

LikeLike

I was thinking along the same lines as above. It is an avenue pursued in Trivium21 and other writing which considers the current curricula at all levels. I am concerned at some of the inconsistency in knowledge shown as students arrive at my door in Y7 and it seems that the academic rigour provided by KS2 varies greatly.

Dr Ken is a guru who speaks most persuasively and in my former incarnation as an opera singer I might sympathise, but to suggest no hierarchy seems to miss the point that without a secure foundation of knowledge, students will struggle as they get older. Yes, maybe Mary is a dancer rather than an academic, but if she is encouraged to ignore the development of her vocabulary and her language skills, this will not help her communicate orally or in writing when she is older. She still has to function in the outside world after her dancing career, tragically cut short by injury at the age of 27.

Creativity is not play and is not something which should replace learning: the two go hand in hand. A creative solution to a business problem does not involve those involved expressing themselves in finger painting, rather it shows the value of a level of learning which allows all to move away from overused paths of thought and to imagine a genuinely new response. With no deep knowledge of their particular area, such a solution will not be forthcoming of of long duration. At school, thd students who are able to think creatively and deeply about Literature (say), are those whose deep knowledge of the Art and its myriad ideas has been built over time. Not by play, masquerading as creativity, but by creative approaches to learning.

LikeLike

Thank you so much for this comment, Jonathan. I think you may have expressed what I was trying to say far better than I did!

LikeLike

I like this and agree with most of it. Where I disagree is at the point where you say a school should teach ‘disciplines’. My disagreement goes back a long way to the early medieval times when a distinction was made: should we teach liberal arts or disciplines? Crucially the decision was made to teach liberal arts. Disciplines point towards one way of doing things and educating in this way is akin to training in which you replicate what has been done before. It has its place mind. Arts begin with constraints, rules, ways of doing but end up with a variety of different outcomes, they result in freedom, a freedom born from knowledge. In the liberal arts you use the knowledge of the traditions of subjects in order to renew or make new, not to replicate.

LikeLike

Ah, that is a very good point, Martin. I think I may have used that word to emphasise the status of the academic study…rather than considering what an ‘academic discipline’ actually consists of. You’re correct, although perhaps there could still be a place for some ‘disciplines’, as you define? Thank you so much for commenting. I’m very pleased you like the blog – this is a subject that is very close to my heart.

LikeLike

(background; I did Latin & Greek GCSE + A-level + a Classics degree at King’s and now tutor Latin & Greek for Comm Entrance & GCSE)

There is undeniably a huge amount of room at the top left by terminally unambitious curricula. GCSE seems to be where it goes wrong in the Classics. The Common Entrance exams, sat by 13 year-olds trying to get into the major private schools, mandate Latin (Greek is optional). There are 3 levels, with the highest (level 3) being mandatory for the best schools. Level 3 is not very far off GCSE in terms of grammar that must be learnt, whilst the scholarship exam (sat by the brightest boys) is almost indistinguishable from an unseen translation paper at GCSE. Essentially, given reasonable teaching, you could do the GCSE a year after Common Entrance Level 3 with minimal difficulty, assuming a good level of intelligence. Instead, an entire year or two gets wasted before the kids eventually do sit the GCSE, which is not an especially challenging exam. I’ve taught Year 7s (the kids are bright and this is 1-1, but still) to near GCSE-level Latin with one hour a week.

A-level is more reasonable, but again not especially challenging. There is insufficient English to Latin translation (in fact I think you can get away with none). It would be fun if the double-translation technique employed by Ascham above could also be worked in somehow. The exam would be much harder, but also far more rewarding.

Instead, the challenge of A-level Latin & Greek comes in digesting these ridiculous set texts. Essentially you learn a very large chunk of Cicero or Herodotus by heart, translate a part of it on demand, and then write brief essay questions about various aspects of the text. It’s a memory challenge, nothing more, and requires minimal to no translation skills if your memory is good enough. These set texts comprise an exceedingly large % of the marks available. At most, they should be worth 20%.

Ironically, doing as I suggest would make the subject harder in some ways but less time-consuming in others, because learning all these set texts is such a boring slog. Given a sufficiently rigorous background in grammar, it would certainly decrease the burden on students.

But of course, no one has that background. Here the textbooks and teaching methods are largely at fault. The old classics (Kennedy’s Primer etc) have been supplanted almost entirely by the Cambridge and Oxford Latin courses, which are dire. They do not teach grammar; the approach seems to be to try to make the poor kids figure it out for themselves. My fiancee, Anna, was taught using the Oxford Latin course and described it as clearly written by people who hate Latin. Nicholas Oulton’s “So you really want to Learn Latin” is an excellent modern 3-part course, but all too rarely used in my part of the world. We could so easily push kids so much harder and faster, but are hampered by lousy teaching & worse teaching tools.

The result of all this, of course, has been a huge collapse in standards at universities, with rampant grade inflation taking place there too. Not just for Classics, but for almost all languages. But that’s a story for another day…

LikeLike

Thank you for this detailed comment, Andrew. The gist of what you say is what I suspected would be the case, but I have limited direct experience of this. I’m absolutely certain we could be offering our kids far more. In English (my subject) I have put PRU pupils through a GCSE course in 12 months. Thank you, again. I very much appreciate this input.

LikeLike

I love this – of course. For a start I have spent the summer reading about Elizabeth I and I also feel exactly the same about the unambitious nature of primary education. My eldest daughter showed little potential in maths but by teaching her at home, mainly half an hour a day in the holidays over the last few years, she will probably be ready for her maths GCSE by the end of year 8. The same would be possible with most children. I’m not suggesting all kids need extra homework but when my son comes home from school he may tell me maths involved taking his turn in a group to roll a dice and make number sentences. So in the day at school he will have done possibly four calculations. He comes home and in a twenty minute after school maths slot he will do 80 or more. He then goes off for an intense session of trains, lego or to dive into whatever rich fantasy he is currently concocting. I am sick and tired of being told that my children are relatively behind with spelling as if it is a developmental issue when they have done precious little spelling work and none that ensures they keep practising previously learnt words. It is more of a miracle they can spell at all given how little focus it has.

It is false to suggest that rigorous teaching is either impossible, cruel or at the expense of the benefits that may be gained through playing.

LikeLike

Thank you, Heather. Yes, I’m absolutely convinced that almost all kids are capable of more than we ever give them the chance to show. I’ve had a few people suggesting that Elizabeth was gifted. This may be the case, but how can we discover full potential if we don’t educate to that level? I also feel kids could be doing far more academic stuff in KS1. This is definitely not a popular stance, I know. Thank you, again for the great comment.

LikeLike

Pingback: More matter, with less art | Horatio Speaks

I see a huge range of knowledge and understanding about teaching reading, spelling and handwriting in Reception, Key Stage One and Key Stage Two. Most schools say they ‘do’ Letters and Sounds as their phonics programme – but it is not a programme – just a detailed framework. That means that teachers have to translate Letters and Sounds into a core phonics programme to be able to provide rigorous phonics practice in reality. This translation varies from school to school and teacher to teacher – but I see many things that could be so much better understood, taught and learnt. There are patterns of provision that can be seen in Letters and Sounds schools – but what a pity people didn’t recognise way back in 2007 that this was not a ‘high-quality programme’ (as was claimed) but a ‘detailed framework’.

You mention spelling – I think we have a very long way to go with the teaching and learning of spelling – it’s still ‘chance’ as to the methods and materials used – and the type of teaching and ethos for supporting spelling whenever pupils are writing. I don’t think we yet know what is possible.

I went into teaching priding myself on being a ‘creative’ teacher. After many, many years in the profession I am totally convinced that children need to be taught well in all manner of basic skills – and knowledge – as this underpins creativity and empowers children. I’m not advocating lessons in Latin or Greek – just better training and teaching in the English language.

I agree entirely, 100%, re the comments about lack of sufficient practice of maths in terms of ‘quantity’ of calculations practised. I have said exactly the same to someone only this week. But it is the same for reading and writing too. And art. I think we should have masses of art and craft type activities in Key Stage One and Two – leading to as much dexterity as possible.

LikeLike

I agree with you. It seems we have a long way to go before we get things right…maybe there are lessons to be learned from how we did things in the past? I think you’re absolutely correct a strong base of knowledge and facts underpins all.

Thank you so much for commenting, Debbie – always a valuable (and valued!) contribution.

LikeLike

Fantastic blog! I have nothing to add apart from the fact that I, too, am increasingly resentful of the ‘academically-lightweight’ education I received during the eighties. Joe

LikeLike

Thanks for the comment, Joe. Much appreciated.

LikeLike

Just to clarify that Reception class is in the Foundation Stage and not in Key Stage 1, and that some children at the end of the Reception year will not yet be 5 years old as their birthdays will fall in the summer holidays. For these children, school is not even statutory until the start of Year 1.

I’m surprised that your daughter isn’t using cursive writing yet – this would be something I would raise with her school as this sounds unusual to me for the end of key stage one. The English National Curriculum says she should be starting to join her letters, as a minimum. According to the Maths National Curriculum, she should also have learned her 2, 5 and 10 times tables, and be on her way to learning the others.

We visited Vinci earlier this year, and went to see the Mona Lisa as well, as my daughter is fascinated by Leonardo da Vinci. I think it would be fair to say that he was a bit of a ‘one-off’ in terms of the level of his genius.

LikeLike

Maybe the expectations of her school are at fault, but I know they have based their report on her SATs results. This would suggest that she is meeting and exceeding national expectations? I think there is no doubt that Leonardo was a hugely talented man, my point is that none of this would have been achieved without long hours of and application. I think we are sometimes guilty of assuming that hard work and academic study are in some way cruel and unnecessary. Thank you for your comment, Sue. It is very much appreciated.

LikeLike

Remember that ‘national expectations’ are just that – a generalisation about the population as a whole, so an average expectation rather than a personalised one. Although it’s not the phase you teach in, it may be worth reading the KS1 National Curriculum so that you can talk to the school from a position of knowledge. If I felt my child was not being sufficiently stretched by her school, I would approach the school to talk to them. There is nothing to stop you teaching her the rest of the times tables at home if you feel she is ready to move on, but she should definitely know 2, 5, and 10 by now.

When we write about a phase we don’t teach in, it’s tempting to base what we say on personal experiences, which don’t necessarily represent the picture of the sector as a whole. This is why it frustrates me sometimes when people talk about play in the early years – because having read the EYFS, Development Matters, and worked in the sector, I don’t quite understand what else they would have us do with 2, 3 and 4 year olds apart from follow the statutory and non statutory guidance.

LikeLike

I think the school are stretching her as far as they are likely to, which is really the point of the blog. We do Maths and Eng stuff at home (partic spelling and reading)…but you’re correct. I’ll check on the times tables stuff.

I think I’m trying to say that it may be possible to introduce some academic concepts earlier than we currently do? I’m not an early years expert, as you say, but I imagine it would be entirely possible, simply from observing my own children – they do seem to absorb information remarkably quickly at a very young age.

Thank you again for commenting. A range of viewpoints is very welcome.

LikeLike

Pingback: Teaching is technology | Horatio Speaks